Choice Design

Choices are the levers of reality. To give players agency - design and present choices.

A choice is different from a test. A test can be passed or failed, while a choice is a fork in the road. A choice presents two or more options, each of which has its own costs and benefits. This makes it impossible for the chooser to select a best outcome. They must commit to an option, and accept its consequences. Situations with a clear best outcome are not choices, they're tests.

In reality, there are innumerable possible options for every choice to be made. It's not reasonable to make a plan for every single possibility.

To deliver choices, the first half of the GM's job is to reduce the number of options down to those with the most unique, interesting consequences. The second half of the GM's job is to frame those options in such a way that choosing between them feels natural.

Priorities

To build choices, ask PCs a selection of these questions to build a palette of their priorities.

- What's the main goal of your plan?

- Does your plan have any secondary goals?

- What factions are involved?

- What obstacle do you want to avoid?

- What's the deadline we're racing against?

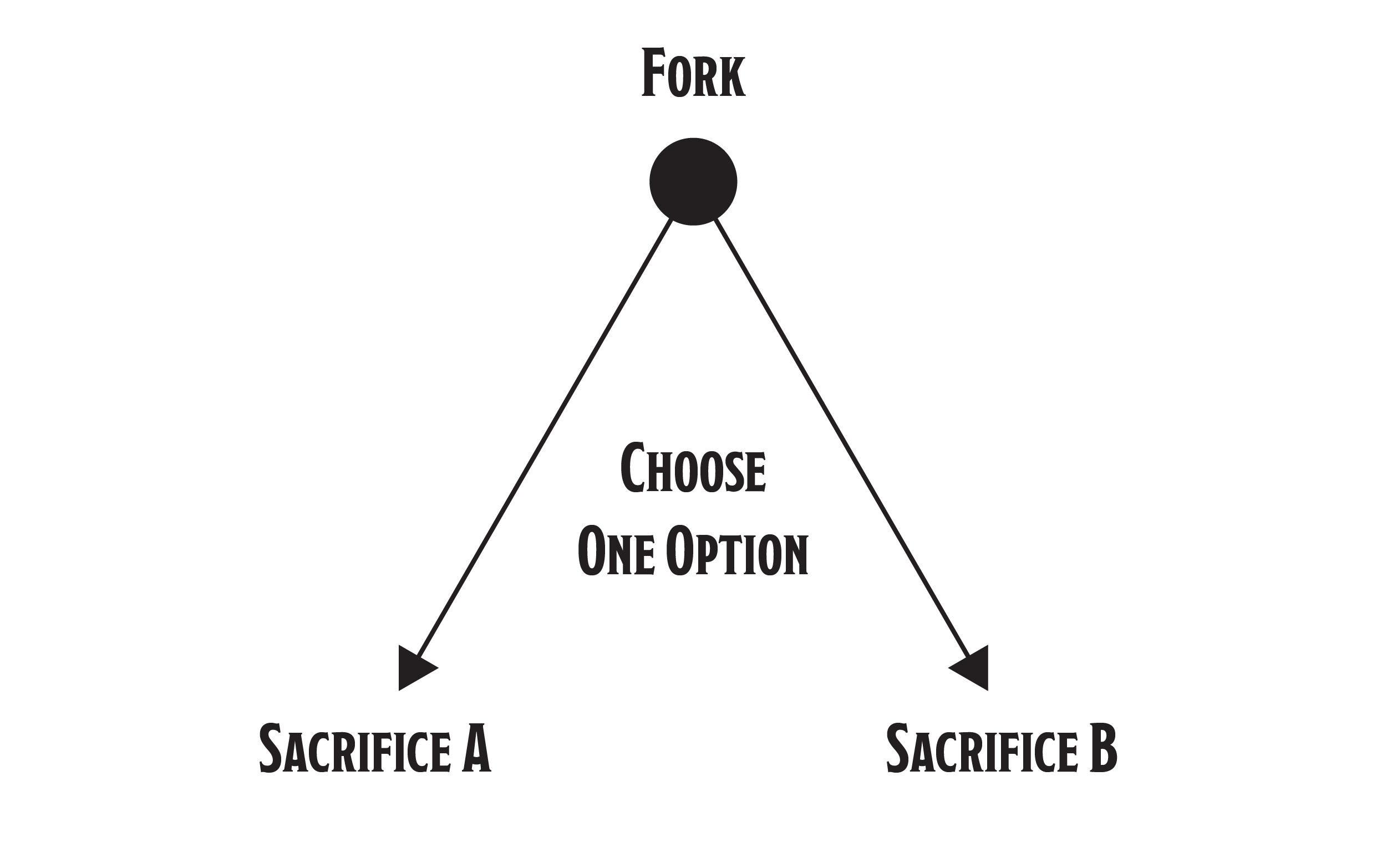

Forks

Forks are the tool to simplify and deliver choices. To craft a fork, pick two competing priorities. For each priority, failing to achieve it is a consequence.

| Priority | Consequence |

|---|---|

| Achieve the main goal. | Fail the main goal. |

| Achieve the secondary goal. | Fail the secondary goal. |

| Avoid the obstacle. | Face the obstacle. |

| Befriend (or appease) faction. | Offend (or let down) faction. |

| Meet the deadline. | Miss the deadline. |

Each option of the fork preserves one priority at the cost of sacrificing the other. When presented with a fork, PCs must choose one priority to sacrifice. Then, the story carries forward the consequence of sacrificing that priority.

Crafting Forks

Choices can have infinite possible options, but forks simplify them down to two competing priorities. These are the fork's two options.

For each option of the fork, envision a situation which would sacrifice the other option's priority.

Then, envision the fork - a physical or rhetorical situation where PCs must choose one option.

Physical fork. Physical forks pressure PCs with the fact that they can't be in two places at once. They are literal forks in the road.

Take the long, safe way (sacrifice meeting deadline), or...

take the quick, dangerous way (sacrifice avoiding obstacle)?

Save the dying victim (sacrifice main goal), or...

chase the fleeing thief (sacrifice befriending faction)?

Rhetorical fork. Rhetorical forks pressure PCs to choose between people, beliefs, goals, and ideas. They are figurative forks in the road, usually prompted by an NPC or a situation which requires a decision.

Will you marry the Prince, uniting the kingdoms (sacrifice befriending faction), or...

will you run away with your lover, plunging the realm further in war (sacrifice avoiding obstacle)?

Physical forks are simple, so they're a good place to start. Once you're comfortable with physical forks, draw on PC and NPC motivations to craft rhetorical forks. Any plan with two competing factions also offers a simple rhetorical fork - which of the factions will PCs support?

When designing forks, it's easy to get hung up on how to make choices natural and unavoidable within the story. For example - what would a fork in the road look like in deep space? This often requires some creativity. Remember that it's okay to present a choice as metagaming information to players.

Before making a choice, players should understand they are sacrificing one priority or another. The GM's job is to convey information about the consequences of the choice, then to put PCs on the spot to choose one option or the other. However that plays out, the group will work it into the story together going forward.

Presenting Choices

When foreshadowing or presenting choices, remember to focus your efforts on contrasting the costs. It's simpler for players to understand that they are choosing between a single priority that they will lose, than it is to understand choosing between multiple priorities that they will preserve or gain.

If we choose (1ST OPTION), we will sacrifice (COST / PRIORITY A), or...

if we choose (2ND OPTION), we will sacrifice (COST / PRIORITY B).

To frame a choice, present the two options of a fork through the story. Qualify each option with what it will cost.

Fail Secondary Goal

Doing this, we won't be able to achieve (SECONDARY GOAL).

Offend Faction

(FACTION) won't like this.

Face Obstacle

Doing this, we'll need to face (OBSTACLE).

Miss Deadline

This will take a lot of time, and we'll be late for (DEADLINE).

Choice Tips

- Grey, not black and white. Choices present trade-offs, with no outcome being a clear winner. The benefit of each option comes at a cost.

- Mutually exclusive. You can only commit to one option of a choice. Frame choices such that committing to one option means not committing to the others.

- Unique and impactful. Choices are meaningful forks in the road. Choosing each different option should yield unique, different outcomes.

- Focused. Focus on a few options, rather than juggling many. Aim for most choices to be between two options at a time. This makes them simpler to understand, less work to plan, and quicker to resolve.

- Foreshadowed. Choices are more tense when you understand the costs and benefits of the options. When possible, foreshadow the trade-offs of a choice before it must be made.

- Unavoidable. Avoidable choices feel less urgent, and can lead to procrastination. When presenting a choice, aim for it to be unavoidable, or urgent in some way.

- 1-2 Per Session. Too many choices is complex to manage and understand. Too few limits agency to influence the story. One good choice per plan is an excellent goal. Three per plan is a reasonable limit.